INTERVIEW: Confessions of the Beautiful Mind and the Echoes Forgotten Tomorrows

[ Exclusive Interview ] ARTIST: Mirza Cizmic

1. I’ve noticed that black cats have been a constant presence in your works, from your earlier pieces to your most recent creations. Is this simply a reflection of your personal fondness for cats, or do black cats carry a particular symbolic meaning in your art? In Western culture, black cats are often associated with mystery or misfortune; yet, in your paintings, they seem to be more integrated into the rhythms of everyday life.

Mirza: The black cats in my work began, perhaps, as quiet witnesses. They appeared almost instinctively (sitting, watching, blending into the scene). Later, I understood that they represented presence without intrusion, like memory itself, always there, silent, observing.

You are right that in Western culture the black cat carries superstition or mystery, misfortune, even witchcraft. But in my world, they are protectors of the ordinary. They bring balance to the tension that often fills my compositions.

I also see them as self-portraits, in a way. They move between light and shadow, never entirely belonging to one or the other. That is how I often feel as a person and as an artist, between places, between times, between identities.

2. In this series of works, I observed that the use of animal elements has become richer and more diverse. While the scenes still carry a sense of absurdity, the animals now seem to blend more subtly into everyday human life. Compared to your earlier works, has the relationship between animals and humans taken on new forms in this series? What kind of metaphorical meanings are conveyed through your choice of animals and their placement within the composition?

Mirza: In this new series of paintings, I wanted animals to feel less like intruders and more like companions, witnesses, and mirrors to human experience. They blend into domestic spaces, interact subtly with people, or even become extensions of the characters themselves. They are quieter, but in their quietness, they carry weight.

The metaphorical meanings are layered. Dog, for example, may reflect loyalty or instinct, but sometimes they are ironic, showing the absurdity of human attachment.

3. In your past interviews, you mentioned that the ghosts in your work represent the threshold between the material and spiritual worlds, symbolizing the unseen forces and consciousness that surround us. Compared to your earlier works, the presence of ghostly elements seems less prominent in this exhibition, replaced instead by more interactions between animals and scenes from everyday human life. Does this shift suggest that you are now more focused on visible, material-world symbols? Or have you found other ways to express that “unseen dimension”?

Mirza: Exactly… that is precisely how I feel. The past is never fully gone! It leaves traces, echoes, and vibrations in everything around us. In some way Ghosts were the most direct way for me to give form to show memory, trauma, and absence. But over time, I realized that the unseen does not need a spectral figure to exist. The unseen world is still there, but I have come to believe that the “unseen dimension” does not always need to appear as a ghost.

4. Throughout your works, the bathroom has frequently appeared as a significant setting. While the bathroom is often regarded as the most private space for cleansing and purification, in your paintings, it seems to take on a more complex and tension-filled role. How do you view the symbolic meaning of the bathroom in contemporary life? Does it represent the boundary between purity and impurity?

Mirza: In my paintings, the bathroom often becomes a stage where contradictions coexist. Cleanliness and filth, vulnerability and intimacy, life and decay. As a space it reveals everything we try to hide.

5. Gender-ambiguous figures appear repeatedly throughout your work, which seems to be more than just a visual choice; it carries deeper meaning. How do you view the significance of this element in the context of contemporary society? Does it reflect your critical perspective on modern human relationships, gender roles, or societal expectations?

Mirza: You could say that these figures are my way of asking. What remains of us when everything that defines us is stripped away? When gender, class, and identity dissolve, what is left is something more essential: the shared vulnerability of being human.

Gender ambiguous figures in my work are not there to make a political statement in a direct sense, but they carry social meaning because they resist definition. For me, these figures represent the fluidity of identity. The space between categories, where a person can exist without being confined.

When I paint them, I am not thinking “male” or “female” I am thinking of being. I am thinking about emotion, fragility, strength, fear, tenderness, qualities that do not belong to any one gender but to the human condition itself. The ambiguity allows the figures to become universal, open; they can be anyone, and at the same time, no one in particular.

In contemporary society, where identities are increasingly negotiated, performed, and sometimes even weaponized, I find that ambiguity is a form of truth. It allows for empathy, for the viewer to project their own understanding onto the figure.

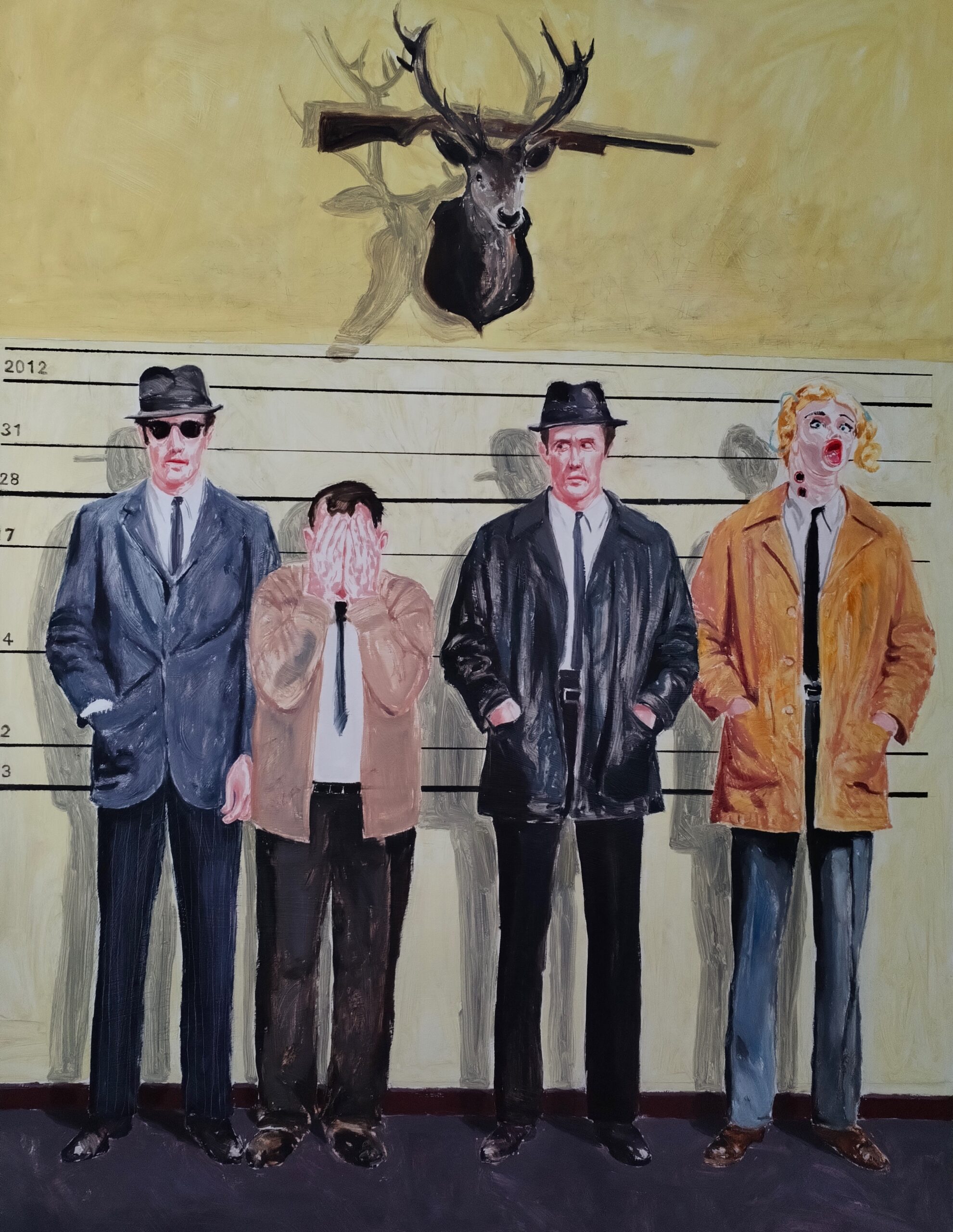

6. When addressing issues of masculinity and gender power in your work, you employ different layers of visual language: some are direct and unabashed, while others are quite subtle. For instance, the arrangement of eggs and sausages on a breakfast plate, or the shadow cast by the deer head in The Alibi, both cleverly allude to male genitalia. Is this progression from “explicit” to “implicit” a deliberate creative strategy? Or is it your way of inviting viewers to discover different layers of meaning within the work?

Mirza: That shift from explicit to implicit is not a calculated strategy so much as a natural evolution. I think as I have grown more comfortable with the subject, I have become less interested in provocation and more in nuance.

I want my work to operate on multiple levels. Someone might first see a familiar domestic scene, a breakfast, a living room and only later realize that the arrangement of objects, shadows, or gestures carries another, deeper implication. That moment of recognition is important to me. It is when the viewer becomes part of the artwork, completing its meaning. The ambiguity, the layering, the quiet wit, they are all invitations. I want people to discover, not be told. Because discovery, like vulnerability, is an intimate act.

7. The presentation of Unwritten Confessions is quite subtle, like a silent scream. On the surface, the priest’s room appears calm and ascetic, yet the Tom of Finland portrait on the wall reveals repressed desires. Does this symbolize the suppression within Finnish society, or even religious societies more broadly, when confronting issues of gender identity and sexual orientation? Or are you also satirizing how, under the entire social system, one’s true self can only be hidden in private spaces, unable to be openly expressed? Could you share more about the deeper meanings behind this work?

Mirza: To me, this work is NOT about Finland or religion, though both contexts are part of it, but about the universal human experience of concealment. Every society, to some degree, asks individuals to suppress parts of themselves to fit in. Unwritten Confessions is about that hidden negotiation AND how we maintain appearances while protecting our most intimate truths. Maybe there is satire in it, yes, but not mockery. It is a gentle irony, the absurdity of a world that demands purity while denying the complexity of being human.

8. In The Last Stand, To N.D., with love, you use a Rothko-like color field background as the setting for a scene of punishment, while in Puppy Dreams, Munch’s The Scream appears in a playful, almost naive way. By bringing these iconic works into everyday or absurd contexts, are you trying to convey a particular message through your choice of these renowned works?

Mirza: In The Last Stand, To N.D., with love, I was inspired by someone I deeply admire. I won’t say who, to keep the riddle alive. I wanted to explore how transcendence and brutality can exist side by side. By painting the act of punishment, I tried to make it feel both sacred and unsettling at once. It reminds me that grace and suffering are not opposites; rather, they are often deeply intertwined.

In Puppy Dreams, Munch’s The Scream “drawing” becomes almost childlike, a visual echo of a cultural memory we all share. It has been reproduced so many times that it has lost its edge, so I tried to place it in a playful, naive setting to bring back its vulnerability. What happens when a symbol of fear becomes a toy or decoration? Does it still hold meaning? That is the question I want to raise.

9. The current global situation is marked by turbulence—wars, political conflicts, and a constant stream of social issues. Your work has long been recognized for its irony and critique of social frameworks. In the face of such rapidly changing times, has this context inspired new directions in your artistic practice? Are there particular contemporary issues that you have been paying close attention to and would like to explore more deeply in your future works?

Mirza: Issues of displacement, identity, and the tension between public morality and private desire weigh heavily on me. I want to explore these not as headlines, but through intimate, personal lenses. How global crises ripple into individual lives, how trauma and resilience coexist.

I want to push these themes further, to use absurdity, humor, and to reveal the contradictions of contemporary life. My goal is not to preach, but to hold a mirror and to show the complexities, the discomfort, and the quiet, often overlooked moments of humanity. We are told that all humans should be equal, yet I cannot ignore that some are treated as “more equal” than others. That tension, that injustice, fascinates me, and it could be a powerful starting point for my future works, a way to explore power, privilege, and the fragile balance between fairness and inequality.

10. This solo exhibition is also one of your ongoing collaborations with Artemin Gallery. As the exhibition unfolds, is there anything you would like to share with the audience? Or perhaps, what kind of feelings or reflections do you hope they will take away after experiencing Confessions of the Beautiful Mind and the Echoes Forgotten Tomorrows?

Mirza: I do not consider Artemin Gallery simply as a gallery; I see it as a home I have never visited. A home where I am always welcome, the place where I can hide if the world becomes too heavy.

As for the audience, I would like the audience to enter these exhibitions without expectation, to allow themselves to feel rather than analyze at first. Confessions of the Beautiful Mind and Echoes of Forgotten Tomorrows are deeply personal, yet they are not just my confessions; they are invitations to reflect on memory, identity, and the contradictions of human experience.

Most of all, I hope people leave with a sense of empathy, a recognition that beneath appearances, carries unseen struggles and fragile moments. And perhaps, for a moment, they will look at the world and themselves and notice what often goes unnoticed.